I wasn’t a fan of this whole “Team of Teams” thing, to be perfectly honest.

That may sound surprising coming from someone who’s worked alongside General Stan McChrystal for more than two decades and is now a Partner at McChrystal Group. But it’s the truth, and like many leaders, my skepticism wasn’t rooted in ideology, but in ownership, ego, and a fear of losing what made our team elite.

This is the story of how that skepticism transformed into one of the most meaningful leadership evolutions of my career and how any leader can help others move from doubt to belief when navigating change.

Phase 1: The Detractor

In 2003, I was an active-duty U.S. Army Major serving in our nation’s premier special operations unit. At the time, I was part of an initiative to stand up a new clandestine capability within our unit, the principal Army component of the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC). General McChrystal had taken command of JSOC a few weeks earlier, and soon we began to hear rumblings of his guidance directing us to work more closely with our SEAL counterparts, including the exchange of Operators, tactics, and techniques. Being on the cutting edge of this initiative, I felt bringing in our SEAL counterparts would slow us down and challenge our role.

On top of it all, I just didn’t care to work with them. They were geographically distant, culturally different, and—from my perspective—likely to hinder or replicate our capabilities. On top of it all, I just didn’t trust them. So, despite General Stan’s guidance and considering I was about four levels below him on the food chain at the time, I continued running my own insurgency against the system and resisting what felt like unnecessary collaboration until I left the unit for graduate school about 10 months later.

Phase 2: The Adopter

A year later, I returned to the Unit to find a transformed Task Force. The fight in Iraq had intensified significantly, but internally, JSOC was evolving too. At the center of it all was a daily Operations and Intelligence Meeting, or “O&I” for short—a live, 90-minute, globally distributed forum where leaders didn’t just brief updates; they shared insights and intent from across the Task Force via secure video teleconference. It was quite an event to watch.

Each day, commanders and leaders laid out their accomplishments, reviewed future priorities, and shared new information about the enemy. But it wasn’t just data. They explained the context surrounding their actions. They shared their “why.”

That transparency enabled logisticians, analysts, and adjacent units to anticipate needs, align resources, and move faster. It wasn’t just a “daily briefing.” It was a deliberate conversation. And it changed everything.

We saw faces. We heard perspectives. We built familiarity and trust. I began to connect with SEALs, Rangers, and others across the Task Force. The friction started to fade.

We weren’t disparate tribes or rival street gangs, fighting for turf anymore. We were working together and fighting the enemy. I also started to hear a new phrase, “We’re fighting like a team of teams.”

No one mandated that term. It emerged organically. But it stuck because it was true. By becoming a Team of Teams, we were becoming more effective.

Over the next few years, I assumed a series of roles at Fort Bragg, in Iraq, and elsewhere, each providing me with a new perspective on how collaboration was transforming the way we fought. Eventually, I transitioned out of JSOC to take on one of the Army’s highest honors: battalion command.

Phase 3: Supporter

Commanding a battalion in the Army is one of the profession’s greatest privileges, and I was fortunate to do so within the storied 82nd Airborne Division.

My unit, the 2nd Brigade Special Troops Battalion, was uniquely complex – comprised of 400 Paratroopers representing 64 different job specialties across four companies: engineer, military intelligence, signal, and headquarters. It'd been some time since I’d worked closely with junior soldiers, and especially not within a conventional Army division, so I spent the first few weeks listening and learning, company by company, soldier by soldier.

What I found surprised me.

While each company was tactically proficient, there was little shared understanding across the unit. Most soldiers, and many of the leaders, had only a vague idea of the competencies of the other companies. Misconceptions were common. Collaboration was limited. We were co-located but not connected.

This had to change.

We were one battalion. We had to operate and fight like one. And to do that effectively, we couldn’t just be a group of specialized teams. We had to become a team. No, we had to become a “Team of Teams!”

Over the next two years, that was exactly what we did.

Drawing on my experiences with JSOC and borrowing some best practices from my friends in the British Special Forces, I set out to break down silos and build a shared consciousness across the battalion.

We started with a “Cross Brief,” where each company showcased its equipment, capabilities, and people. Soldiers engaged with peers outside their specialty and saw for the first time how their work fit into the bigger picture. We followed up with a full-day summit, where we shared training highlights, lessons learned, and the roadmap for the year ahead.

Then we institutionalized it. We launched a weekly “Operations Forum” to keep everyone aligned and informed. We pushed more decision making to the edge, empowering junior leaders to act decisively. Slowly but surely, we weren’t just coordinating. We were operating as one.

Then we institutionalized it. We launched a weekly “Operations Forum” to keep everyone aligned and informed. We pushed more decision making to the edge, empowering junior leaders to act decisively. Slowly but surely, we weren’t just coordinating. We were operating as one.

That cohesion was put to the test when we deployed to Haiti in 2010, not for combat, but for humanitarian relief operations following a devastating earthquake. Conditions were austere, resources were limited, and urgency was high. But my Paratroopers rose to the moment, bringing aid, relief, and stability to tens of thousands of displaced Haitians.

It was a proud moment. The local Fort Bragg newspaper, Paraglide, ran an article that said it all: “2 BSTB Soldiers Become a Team of Teams”.

Phase 4: The Advocate

After my command in the 82nd Airborne, I returned to the JSOC community, and what I found was extraordinary. What began as an adaptive necessity became a deliberate operating system. “Team of Teams” wasn’t just a phrase anymore; it was a practiced discipline, a shared language, and a cultural cornerstone. The Task Force had become a machine, and that machine was humming – faster, smarter, and more cohesive than anything I had seen.

After my command in the 82nd Airborne, I returned to the JSOC community, and what I found was extraordinary. What began as an adaptive necessity became a deliberate operating system. “Team of Teams” wasn’t just a phrase anymore; it was a practiced discipline, a shared language, and a cultural cornerstone. The Task Force had become a machine, and that machine was humming – faster, smarter, and more cohesive than anything I had seen.

Our teamwork was evidenced in the following year when the Task Force executed the operation to kill the infamous terrorist leader Osama bin Laden.

A few years later, the full evolution of this transformation was captured in General McChrystal’s New York Times Bestseller, Team of Teams. But for those of us in special operations, it wasn’t a theory. It was a way of life.

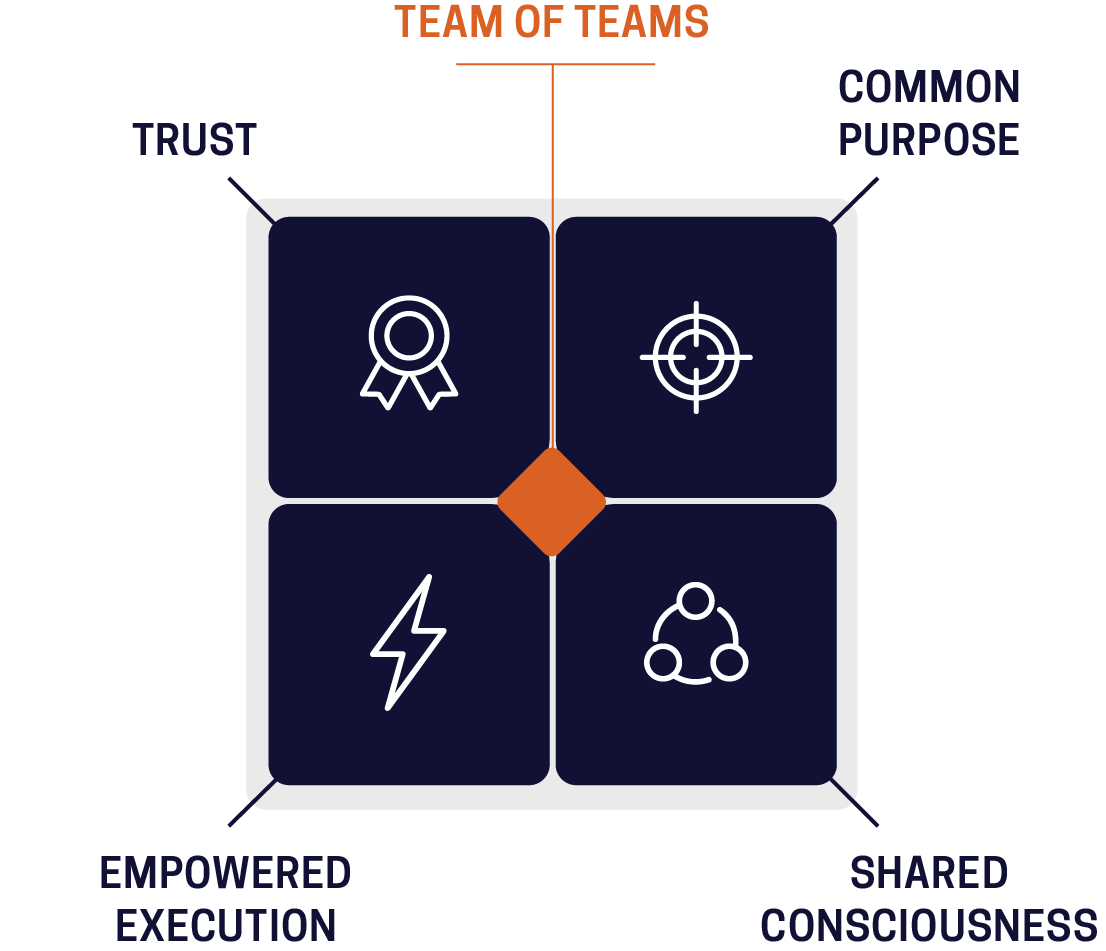

I retired from the Army in 2018. After years of operating within a true Team of Teams, principles like Trust, Common Purpose, Shared Consciousness, and Empowered Execution weren’t abstract ideals—they were instinct. They were muscle memory.

From the Battlefield to the Boardroom

Much to my surprise, life after the military brought me full circle. I found myself working alongside General McChrystal once again—this time, as a Principal Consultant and, eventually, a Partner at McChrystal Group.

However, instead of building high-performing teams on the battlefield, we were helping senior leaders achieve the same goal within their organizations, across various sectors, including oil and gas, public health, pharmaceuticals, and government.

We deliberately guided executive teams through the same transformation we once navigated through trial and error, helping them shift from siloed hierarchies to cohesive, adaptable networks of teams.

We deliberately guided executive teams through the same transformation we once navigated through trial and error, helping them shift from siloed hierarchies to cohesive, adaptable networks of teams.

During the COVID-19 Pandemic, I worked closely with the State of Nebraska’s public health community to apply these principles under crisis conditions. And once again, the model proved its worth.

The Team of Teams approach doesn’t work because it’s a military framework. It works because it’s a human one. It’s about people building trust, aligning around a common purpose, communicating transparently and effectively, and empowering execution at every level.

And when you get those things right, in any sector or environment, the results are transformative, just as they had been for our Task Force.

From Detractor to Advocate

For the past seven years, I’ve humorously told the story of my journey from Detractor to Advocate.

Beyond being my personal journey of discovery, it offers an important lesson.

As leaders, we often drive change because we believe it’s necessary or because we’ve seen what’s possible. But it’s naïve to think that everyone will immediately get on board. That’s not how change works. There will always be skeptics. There will always be detractors.

But if you lead with the principles embedded in Team of Teams:

If you build Trust, Align around a Common Purpose, Create Shared Consciousness, And Empowered Execution at every level,

Then you create alignment. You don’t gain compliance. You cultivate conviction.

And in time, your fiercest detractors become your strongest advocates.

Because the truth is, Team of Teams was never meant to be a destination.

It’s a journey. A continuous pursuit of what’s possible when we commit to deeper collaboration, more transparent communication, and greater adaptability across every level.

That commitment starts with us. No matter where we are on our journey.